prodigy

a person, especially a child or young person, having extraordinary

talent or ability:

a musical prodigy.

There has been quite a bit of social media activity about 11-year old pianist

Joey Alexander. I've been asked about him a bunch of times, presumably because I'm a jazz musician and teacher. So, I checked him out on YouTube. The quick version: he certainly has more chops and knowledge than most kids have, and admittedly more than many grown-up players.

But this got me started asking a bunch of other questions as I tried to pin down exactly how I felt about the entire "prodigy" phenomenon.

Is our collective fascination with prodigies unique to jazz?

Certainly not. On a fairly regular basis, I see Facebook friends posting about some super-young classical pianist, rock guitarist, athlete, chess player, etc. --- all of whom are so young that it seems impossible that someone on this earth so few years could get so good at anything. But perhaps there is something about the nature of jazz, that requires the combination of a high level of instrumental skill and the ability to be spontaneously creative through improvisation, which makes the concept of a jazz prodigy particularly compelling.

Is it good for a kid to get a lot of media attention?

I believe we

all have all the evidence we need to determine that it is not.

Is it good for a young aspiring artist to get this much attention?

Hmmm. Pedagogically, I feel that the risk is in the message being sent. Even if it is not overtly spoken, this quantity of attention sends a young mind the subliminal message that they are already

so wonderful and

so successful that the process of becoming a musician might get stunted, or be altered. They might stop striving, growing, searching, learning, listening, failing, or even having fun. "Wow, if musicians decades older than me aren't playing the Newport jazz festival like I am, I must be really good!"

I'm not saying that

will happen; it just feels like a risk. I'll have more to say on risk and calculated risks another time.

Do child prodigies grow up to become great artists?

Yo Yo Ma and Herbie Hancock were both considered child prodigies. Both have since spent decades as the top practitioners of their craft while also embodying the absolutely highest level of artistic achievement. And, at the risk of grossly understating their accomplishments, both of them have become hugely culturally relevant beyond the realm of the inner circle of musicians. In other words, they connect with "real human beings" who flock to hear them play.

I believe it is important to note that their pre-teen performances or recordings are NOT what made them great artists. Perhaps their early skills helped to get them on the people's radar initially, but it was what they did AFTER their childhood that made them great.

Yo Yo Ma's

Silk Road Ensemble is making some of the most compelling music in the world today. He collaborates with an impressive roster of performers and composers, from a wide variety of cultural backgrounds, and creates something entirely new. And at the same time, his voice in the group is not just as "soloist" --- he's part of the fabric of the group that allows each member to contribute.

In his early 20s, Herbie Hancock moved to New York and made his first solo album, which is when Miles Davis heard him and invited the pianist to join his band. It was with Miles' band that he really started to make waves in the world.

Hancock's success was not just because he "had chops." He was part of a unit in which he played an integral yet primarily supporting role. He was just one member of Miles' now-classic "Herbie, Ron & Tony" rhythm section. Yes, he played

stunning solos in that band, but the group dynamic was what made this rhythm section special. The conversational way they played (and then the interactive way they accompanied the horn soloists) was what made the entire group truly great. This band was certainly greater than the sum of its parts, which is particularly impressive since all the "parts" were already spectacular players individually.

And now in retrospect, it is clear that the recordings Hancock made during his 20s were perhaps just the beginning of his process of becoming a great artist. His Blue Note records are really fun. But I enjoy them even more now that I hear them as part of the long timeline of his music. He has had a long and varied career, making an impressive number of beautiful, soulful, and funky recordings in several sub-genres of jazz, many of which don't actually showcase his prodigious technical skills at the piano. They're just beautiful.

So my answer to this question is: Yes, prodigies can grow up to be great artists. But their prodigious childhood skills are not what made them great.

But then again, does a young prodigy's future as a great artist even matter?

In other words, if a prodigy ultimately does not become a great artist, was all the attention a bad thing?

Let's look at the story of saxophonist Christopher Hollyday. When I was a teen, Chris was being hailed by the music industry as one of the upcoming "young lions" of jazz. When he was around 16, in the late 80s and early 90s, he got a deal to make some records. There was quite a buzz surrounding him. He toured with Maynard Ferguson for a while, but after that pretty much fell off the radar in terms of the national jazz scene.

I hadn't thought a lot about Mr. Hollyday in the past 20 years, but I recently came across

an interview with him that impressed me quite a bit. I learned that he went back to school to earn a teaching degree, and has spent the years since then as a band director in California. He still plays and teaches. I would absolutely consider that a successful career that he should be very proud of. I suppose the phrase "he still plays and teaches" basically describes me too, and I'm good with that. So I'm not entirely sure that "future world-renowned greatness" always matters when it comes to the question of prodigies.

I'm sure I'll say more on that in the future, though.

Back to Joey: does he deserve this level of admiration?

My reaction to this will probably sound like a cliche to generations younger than me (what I'm about to say certainly

sounded cliche when I heard people say it). Nonetheless, here goes:

I find unadulterated youthful energy joyous to behold, and for a while I can enjoy his music on that level. If I DIDN'T enjoy hearing young people make music, I wouldn't have become a music teacher. But if I only wanted to experience unbridled young life force, I'll watch a bunch of kids running around a playground. I find it much more appealing hear how a performer's life, age, and experience influence their art over time. The people you meet and the grand successes or colossal failures in your life influence your music. Having kids of your own changes your music. Losing a parent changes your music. Studying art and history change your music. Reading novels changes your music. I want to hear all of it, so I feel like I'm part of their joy and art.

One of my most frequent themes (my students may be sick of hearing me talk about it by now) is that jazz is

more of a process than a product. For me to want to follow an artist, to want to delve into their artistic progression, to buy into their entire THING, their music has to run deeper and go longer than only "having an unusual amount of chops for their age." That might pique my interest initially, but won't keep me coming back for more. Not quite yet.

Might my feelings on this be related to my own professional jealousy?

Yeah, I'm willing to admit that. I was jealous of Christopher Hollyday back in the 80s. And sure, I'd love to have Wynton take me under his wing, talk about me, have record labels knock at my door, and to have massive international jazz festivals invite me to be a headliner. I'd love for the world to acknowledge my

creativity, my

amazing playing, my... my...

...Uhhhh... I see that I've kinda gone off the rails here.

I have a successful career in music, so to complain about this kind of thing would really be criminal. I have a wonderful teaching position. My students and colleagues like me and respect my music. But I admit when I hear about a jazz prodigy, it's still hard to stop my brain from occasionally running various "what-if" scenarios, and to wish I had people doing all that time-consuming behind-the-scenes grunt work needed to spread my artistic vision and further my career. I hope you'll forgive me for that.

So, what the heck was I doing when I was 11 years old?

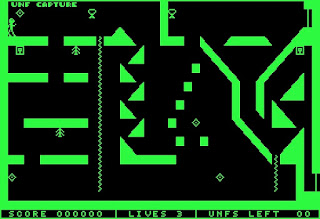

I had started playing saxophone, and I was just starting to write music. But mostly, I was spending hour after hour sitting at my Apple II computer, programming little games, using BASIC and 6502 machine language.

My dad had gotten me started programming, but most of the impetus to do it was my own. I think my parents (and perhaps some other folks too) thought I was something of a "software prodigy." Oh, I loved music too, but I was so dedicated to programming that around this age that I once gave a lecture/demonstration to

our local Apple users group on Apple II machine language graphics programming --- the memory map, which memory locations represented the various pixels on the screen, how to "poke" the memory to draw shapes and colors --- y'know, that kind of stuff. Years later, my dad told me that an attendee from Kodak who saw my demo had apparently offered me a job on the spot (well, at least after I finished high school). I'm glad my dad didn't tell me about that at the time. I'm pretty sure that would not have been a wise move.

When I think back on the amount of sheer time I devoted to programming, I wonder what if I'd started using all that 11 year old energy to practice 4-5 hours a day.

Oh, sheesh, there I go again --- talkin' what ifs...

The truth is that I wish Joey nothing but artistic and career success as a jazz pianist, if that's how he ultimately decides to move forward in his life. A musical career is not an easy road to travel, so I suppose any help he gets along the way can't entirely be a bad thing. The teacher inside me would surely be happy to help him out in any way I could, too.

Keep on keepin' on, Joey.